The story so far

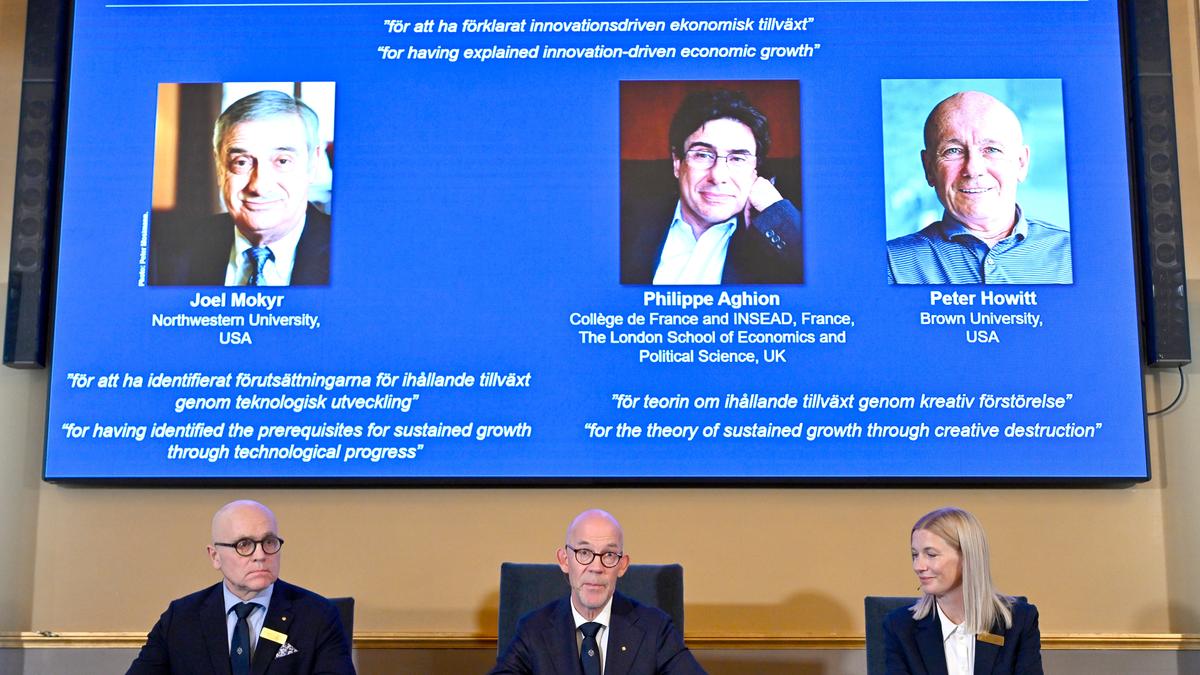

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences on Monday (October 13, 2025) announced that it had decided to award the 2025 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel, popularly called the Nobel Prize in Economics, to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”. One half of the prize goes to Mr. Mokyr, while the other half will be divided between Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt.

Who are the winners and why were they awarded?

Joel Mokyr was born in 1946 in Leiden, the Netherlands. He completed his PhD in 1974 from Yale University in the U.S., and is currently a professor at Northwestern University. According to the award citation, he won the prize “for having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress”.

Philippe Aghion was born in 1956 in Paris, France. He completed his PhD in 1987 from Harvard University and is currently a professor at Collège de France and INSEAD, Paris, France and The London School of Economics and Political Science, U.K.

Peter Howitt was born 1946 in Canada and completed his PhD in 1973 from Northwestern University. He is currently a professor at Brown University in the U.S.

Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt jointly won the other half of the award “for the theory of sustained growth through creative destruction,” the award citation said.

What was Joel Mokyr’s work in this area?

To understand the work of all three economists, one must first understand the fact that global growth has been unusually sustained over the last 200 years, following centuries of stagnation. The work of all three economists, in different ways, tries to answer what happened in the last two centuries that set them apart. This, therefore, also creates a model of sorts for sustained growth into the future as well.

Through his research in economic history, Mr. Mokyr showed that a continual flow of “useful knowledge” is necessary for sustained growth. This useful knowledge, he theorised, has two parts: propositional knowledge and prescriptive knowledge. Propositional knowledge basically has to do with looking at the natural world and figuring out why something works. Prescriptive knowledge refers to actual practical instructions, drawings or recipes that describe what is necessary for something to work — like an instruction manual.

He argued that, prior to the Industrial Revolution, the world’s leading innovators had a good command of propositional knowledge. That is, they had strong theories, after observing the world, of why things worked. This propositional knowledge, however, did not rest on a bedrock of prescriptive knowledge. Without the latter, it became next to impossible to build upon existing knowledge.

This changed in the 16th and 17th centuries, Mr. Mokyr argued. Scientists began include precise measurement methods and controlled experiments in their work, and began to insist that results be reproducible. This, he said, led to improved feedback between propositional and prescriptive knowledge.

Some examples of how this led to “useful knowledge” was how the steam engine was continuously improved thanks to insights gained around that time into atmospheric pressure and vacuums, and also advances made in steel production due to a greater understanding of how oxygen reduces the carbon content of molten pig iron.

What are the implications on policy from this work?

The policy prescription of Mr. Mokyr’s research was twofold. The first was that new ideas would become reality only if practical, technical and commercial knowledge was abundantly available. Without these, he argued that even brilliant ideas such as Leonardo da Vinci’s helicopter designs would remain on the drawing board, as they indeed did.

He argued that sustained growth first took place in Britain because it was home to many skilled artisans and engineers who were able to transform ideas into practical, commercial products, which was vital in achieving sustained growth. The policy implication from this is that governments must invest heavily in skilling if they want sustained growth.

The other factor — and policy prescription — for sustained growth, according to Mr. Mokyr, was that society should be open to change. Innovation invariably creates winners, but it also creates losers as new technologies replace existing ones. This can often lead to resistance to change from established interest groups.

What was the work of Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt?

These two economists took this idea of “creative destruction” — where innovation leads to gains, but also the destruction of the incumbents — and created a mathematical model to capture it. They showed, through maths, how technological advancement leads to sustained growth.

The basic assumption is that economies include companies that do research and development to create a product that they can patent, thereby creating a monopoly for them and putting them at the top of the chain. However, a patent can’t stop another company from also investing in R&D and coming up with a new product. If that new product is better, it will replace the incumbent and the profits will now flow to the new company.

The model developed by Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt can be used to analyse whether there is an optimal volume of R&D, and therefore economic growth in a free market scenario where there is no political interference. They found that there were two competing trends that made it difficult to arrive at an answer.

Should governments subsidise R&D and by how much?

The first trend is that, when a new innovation comes in and replaces another, the benefits from the replaced technology still continues to flow to society, even if the company that developed it is no longer making profits from it. In other words, technology that has been outcompeted has more value for society than for the company that developed it. This makes it imperative that R&D be subsidised so that companies aren’t discouraged from it.

However, the other competing trend is that when a company comes up with an innovation that rises to the top of the chain, it starts receiving the bulk of the profits even though the actual improvement might have been incremental over the older technology. For society, the gain from this new technology is limited because it is only a relatively small improvement over the older technology. In such a scenario, investments into R&D might be too high from a societal point of view. Therefore, under this trend, R&D should not be subsidised.

The answer to the question of how much R&D needs to happen will of course vary depending on the society and economy in question. However, Mr. Aghion and Mr. Howitt’s theory can be useful for the understanding which measures will be most effective in arriving at the optimum R&D level for sustained growth.

Published – October 13, 2025 05:13 pm IST